We can have affordable housing: why it’s scarce and how to fix it - part 2

To end artificial scarcity, you need to allow stuff to get built

In Part 1 of this topic, I tackled the myths around housing affordability in Los Alamos, making the case that our local housing crisis isn’t entirely the result of greedy developers or economic forces out of our control. Instead, it's largely driven by decades of restrictive zoning and land-use policies that favor single-family homes and prevent the building of more affordable housing types. (If you missed it, you can read it here.)

Now let's turn our attention to the supply side of the solution: how we can realistically increase housing availability and create lasting affordability.

The supply side of the solution

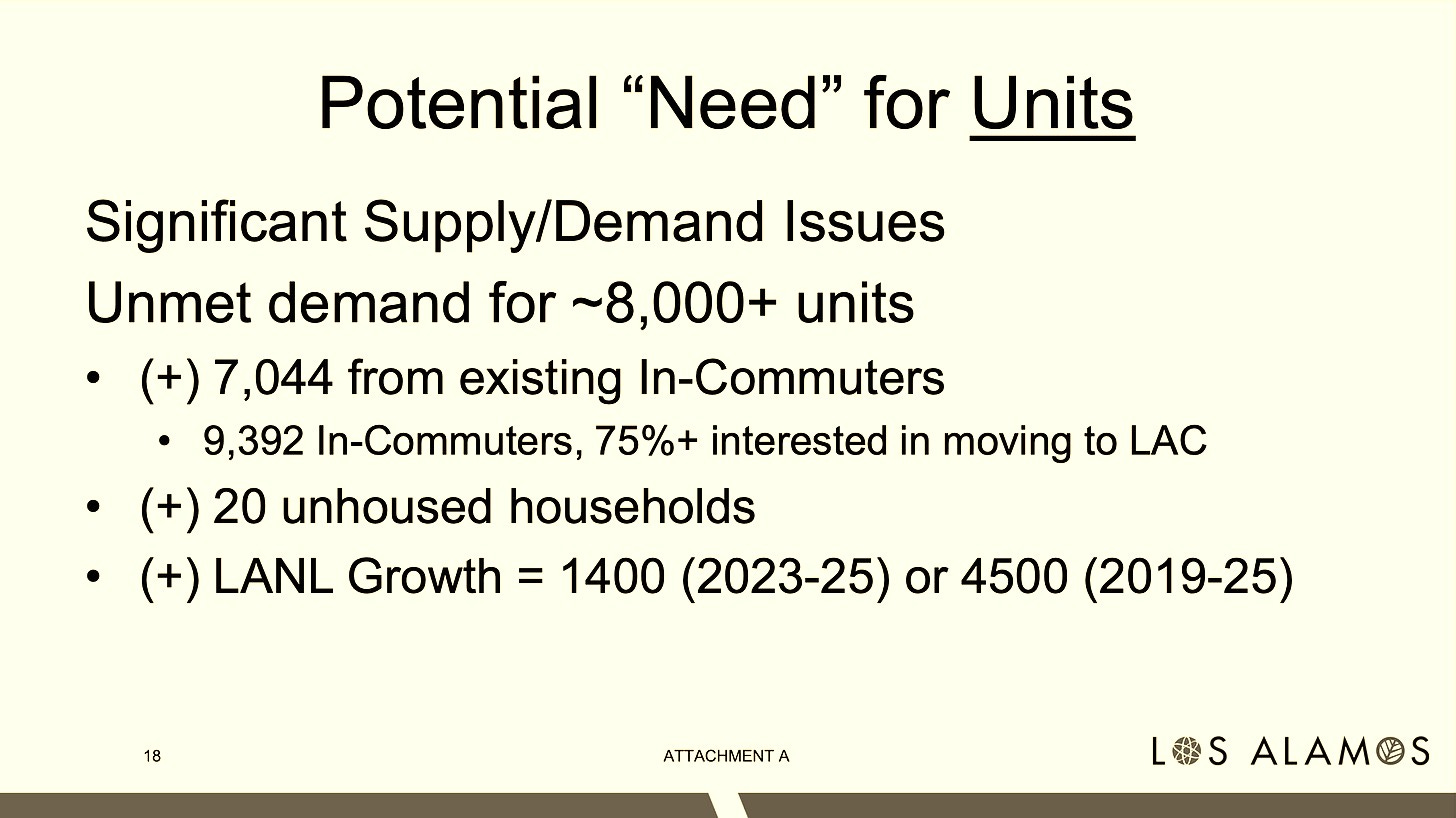

The Los Alamos Affordable Housing Plan recommends a minimum density of 10-15 dwelling units per acre—significantly higher than our current typical densities—to achieve affordability goals. With so little land available for residential development, density isn’t just one approach; it’s the only approach.

What does this mean in practice? Not 20-story high-rises—we’re never going to be London or Manhattan—but a return to the kinds of neighborhoods that existed before exclusionary zoning took hold. It means allowing duplexes and triplexes that resemble single-family homes from the street. It means permitting cottage courts and townhomes by right—without special meetings, variances, or endless traffic studies. And yes, it means encouraging the most density—taller buildings—in our neglected downtowns. (Which will revitalize said downtowns! More on this another day.)

Readers who live in Los Alamos see examples of “missing middle” housing daily; they just may not recognize it as such—these are the quads, duplexes, and small apartment buildings constructed during the Manhattan Project era. According to local historian Craig Martin’s book “Quads, Shoeboxes, and Sunken Living Rooms: A History of Los Alamos Housing,” these buildings were built out of necessity and kind of in a big scrambly panic to alleviate a housing supply crunch that, really, should have been predictable considering the war effort involved. This housing remains today and is among the most affordable in this unaffordable market: not so much because the houses are old as because they offer gentle density, making good use of limited land.

Today’s equivalent attempts face years of delays, enormous costs, and often fierce neighborhood opposition. Consider the Canyon Walk Apartments, which took five years from conception to completion due to all manner of problems, including regulatory hurdles, multiple public hearings, and repeated redesigns.

A healthy market allows new housing when people want it, where they want it. But exclusionary rules—“luxury zoning,” “single-family zoning,” whatever you want to call it—stop that from happening. Once people get their own house, there’s a “pull the ladder up behind you” impulse that kicks in, AKA “my house is the last house that should ever have been built in this town!” We have codified this impulse into our regulations.

Without that regulatory layer, when labor, materials, and financing were cheaper, we would have been ready for the Lab expansion we knew was coming. The Lab, which foresaw the problem, begged the county to get building. We could’ve built townhomes, duplexes, quads, and apartments by right. No lengthy approvals, no multiple traffic studies, no height restrictions, no parking mandates, no parcel-by-parcel fights where people scream that townhome buyers or (heaven forbid) apartment-dwellers are going to Bring Crime and Hurt The Children!

A community choice: abundance or scarcity

Many factors make housing unaffordable, but exclusionary zoning is the original sin.

That’s the first myth I want to bust: housing unaffordability is not (or at least not entirely) the fault of some outsider, mustache-twirling developer.

It’s us.

That’s the bad news. Housing unaffordability is, fundamentally, on us—the people who live here.

But that’s also the good news! If it’s on us, that means we have the power to flip the script.

Los Alamos is at a pivotal moment. In 2025, we’ll begin updating our Comprehensive Plan—the guiding document that shapes how our community grows and develops. According to the 2024 Polco survey, residents are deeply dissatisfied with the county’s approach to planning and community design. Only 22% approve of our residential and commercial growth planning, and only 32% rate our land use, planning, and zoning positively.

We have an opportunity to choose abundance over scarcity. To create a community where teachers, healthcare workers, and service employees—who earn an average of $49,133, less than one-third of the average LANL wage of $160,000—can afford to live where they work. Where young families can find starter homes. Where seniors can downsize without leaving the community they love.

This isn’t just about housing—it’s about the community we want to be. Do we want a diverse, vibrant town with thriving businesses and public spaces? Or do we want to continue down the path of becoming an increasingly exclusive enclave accessible only to those with the highest incomes?

What you can do

If you’re convinced that Los Alamos needs more housing options, here are concrete steps you can take:

Learn about zoning in your neighborhood. Understanding what can and can’t be built is the first step toward advocating for change.

Attend County Council meetings when housing issues are on the agenda. Council listens to the public (no, they really do; I’ll write more on this later), especially when it comes from unexpected voices supporting more housing.

Talk to your neighbors about the benefits of allowing more housing types in your neighborhood. Many people don’t realize how current rules limit options for downsizing seniors, young families, or their own adult children who might want to stay in Los Alamos.

Get involved in the 2025 Comprehensive Plan update process. This once-in-a-decade opportunity will shape Los Alamos for years to come: I will have more on this initiative soon.

Support local businesses that are struggling with staffing shortages due to housing constraints. Ask them how housing affects their ability to operate—and amplify their voices.

For county and state leaders reading this: You have a clear mandate: Los Alamos residents want more housing options (their top priority in the Polco survey). They want a vibrant downtown (only 15% rate it positively now). They want governance that tackles hard problems (only 38% approve of the county’s current direction). Bold action on land-use reform would address all three—the 2022 Chapter 16 update was just the start. The 2025 Comprehensive Plan update is your chance to create a true legacy of abundance rather than the artificial scarcity of the status quo.

Scarcity is a choice

The housing crisis in Los Alamos isn’t inevitable—it’s the result of specific policy choices we’ve made over decades. Homebuilders want to build housing where people want to live. Our regulations have prevented them from doing so. This mismatch between supply and demand isn’t some mysterious economic force—it’s the predictable outcome of rules that privilege certain housing types over others, political processes that advantage existing homeowners over newcomers, and laws that force scarcity over abundance.

Housing is not, I promise, the only thing I’m going to write about. But as that Polco community survey shows, it’s arguably the most pressing issue the county faces right now. Whether it’s how housing costs impact the cost of living, or how wildfire risk impacts housing, or how housing availability plays into climate and road safety, the roof over our heads is fundamental to everything. As we go along, I’ll explore wonky details of housing economics, look into how subsidized housing plays into affordability, and examine some specific policy solutions that either are working or could work for Los Alamos. For now, I hope I’ve helped dispel some of the myths that cloud our understanding of how housing affordability actually works and how we might fix it.

If there’s a local-governance policy topic YOU want to see me dig into—housing or otherwise—let me know in the comments!

I'm interested in the supply theory and I definitely agree that zoning can be too restrictive. But based on my own limited and anecdotal experience, supply doesn't always mean affordable. I grew up in Loudoun County in Northern Virginia where the population has almost quadrupled in 25 years. They've allowed all the types of housing you describe but the result was more people coming, and prices are as high as ever for every housing type.