My dog was bitten by a rattlesnake: What I learned

Sixth rattlesnake/dog bite this week alone, vet told me

This post does not really fit the theme of this Substack but you know what? Nobody will be mad about that, and the information may be useful. Which is my ultimate goal—to share useful information.

Yesterday, a rattlesnake bit my dog Ziggy in the face during a hike. He’s recovering now, thanks to fast action and expert vet care, but I wanted to share what I’ve learned—because a few articles I read years ago helped me stay calm and act quickly when it happened to us.

It was a cool, cloudy May day, after days of rain and even some snow. We were on a steep, rocky trail (Pipeline, near the water tank) around 11:30 a.m. when Ziggy nosed into a bush a few feet away from me. I heard him cry out, then heard that unmistakable rattle. First the yelp, then the rattle: there was no warning. His nose was bleeding. I didn’t see the snake, but I knew what had happened.

I didn’t try to carry him—we had a steep descent, and I had another dog with me—but I kept thinking, “His airway is going to swell shut.” We ran back to the car as fast as I could run. This is not standard protocol, I learned—see more below. Ziggy seemed fine on the way down, even fine when we arrived at Ridgeview Vet about 20 minutes later. But as soon as we walked through the door, the swelling began.

The vet gave him antivenom (also known as “antivenin”) immediately and started IV fluids. He was clearly uncomfortable but stayed alert, breathing normally, and didn’t show signs of shock. But because there’s no overnight vet in Los Alamos, I transferred him to the Santa Fe emergency clinic (Mosaic) as a precaution.

At the animal ER, they saw clear fang marks and suspect he may have been bitten twice—once on the face, possibly once on the chest. They said it looked like a large snake judging by the distance between each fang mark, but possibly it was a “cool weather bite,” meaning the snake might have been sluggish and not delivered a full venom load. Ziggy’s bloodwork looked good, and they were cautiously optimistic.

The vet at Mosaic said it was the sixth rattlesnake bite they have seen this week.

What I think I did right

I know what a rattlesnake sounds like and didn’t wait to see if it “got worse.”

I knew where the nearest vet was with antivenom and drove straight there.

I didn’t try to be a hero by carrying a 55-lb dog down a cliff trail, risking injury to both of us.

Standard advice says to carry the dog if you can and keep the bite below the heart to slow venom spread. But we were on a steep rocky trail, and I had another dog with me. I could carry Ziggy very slowly—or get him to the vet quickly. I chose speed. We made it to the vet in 20 minutes, and this strategy seemed to work. Every situation is different, and you’ll need to make the safest, fastest choice you can in the moment. If your dog is small, you are strong, the terrain is forgiving, or you have help, carry them. But if you can’t, don’t freeze—just move with purpose and get help fast.

What else saved us: friends

I can’t recommend this enough: Have friends. Call on them. I called my friend Angie as I was running downhill—she’s a doctor and a dog person, but more importantly, I knew she’d stay calm. I could not call around looking for antivenom and run full tilt at the same time: I needed someone who could take over the logistics, because my own system was overloaded. Angie made the vet calls, found one with antivenom, and told them I was coming. By the time we arrived, they were ready. That made all the difference.

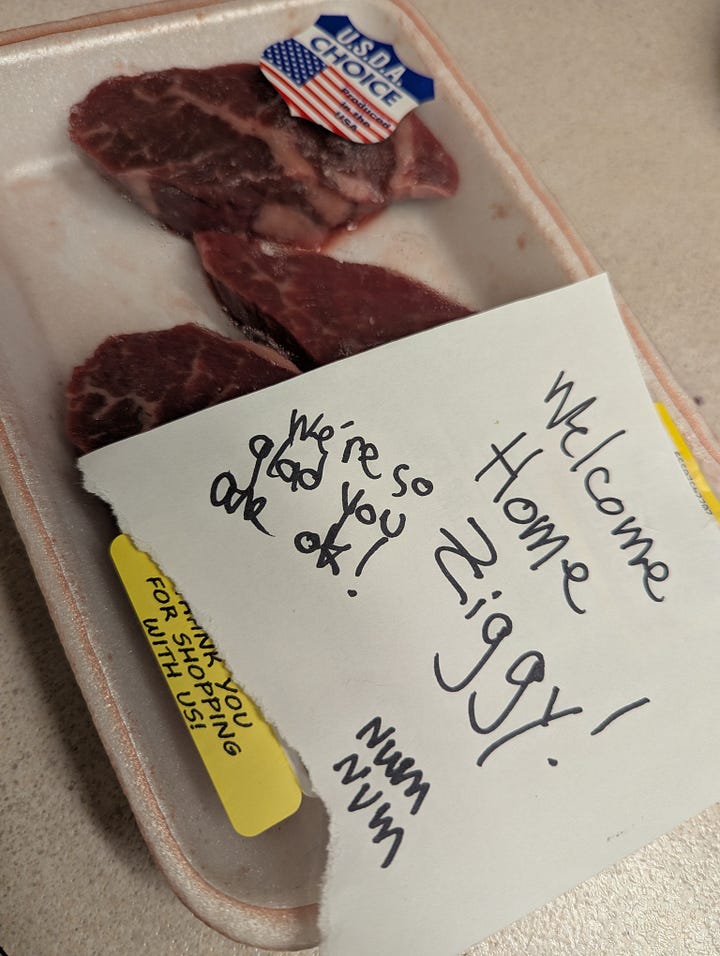

Another friend watched the second dog for me. Yet another dropped everything, left work, and drove with me to the emergency vet in Santa Fe. I didn't hesitate to ask, and they didn’t hesitate to help—just as I would for them. Other friends rallied for us in other ways: emotional support, physical support, messages, love. My neighbors brought Ziggy some steak. 😭

If you’re reading this and thinking you’d “hate to impose,” I get it. But in a true emergency, your friends are your backup system. Use them. That’s what the good ones want.

What I wish I had known or done

That rattlesnakes can be active even after days of cold rain. Everyone I spoke to was surprised they were out

I should have taken his collar off as soon as possible—especially with a face bite

That swelling can be delayed—it didn’t start until 20+ minutes after the bite

That a rattlesnake-bite vaccine exists (but it may not be very effective)

That aversion training exists (but for nervous dogs like Ziggy, it can backfire)

How rattlesnake bites work, and why speed matters

While the techs stabilized Ziggy, the vet came out to explain how rattlesnake bites work. I really did not want to sit and listen at that moment, but she wanted me to be very clear on what to expect and why it’s so important to get treatment fast. So, I’m passing on what I learned. People get bitten, too: everyone in rattlesnake country needs to know this.

Rattlesnake venom is nasty stuff. It contains a mix of enzymes, proteins, and toxins that:

Damage tissue (leading to swelling, bruising, and sometimes tissue death, aka “necrosis”)

Disrupt blood clotting (causing internal bleeding or excessive bruising)

Affect the cardiovascular system, potentially causing shock

In some cases, affect the nervous system, leading to weakness or trouble breathing

These effects don’t always show up right away. That’s why dogs can seem OK after the bite and then crash later—especially if the venom starts interfering with their ability to clot blood or maintain blood pressure. In Ziggy’s case, he seemed fine for 20 minutes, then the swelling started.

Antivenom works by neutralizing the venom toxins, but it’s most effective when given early. It can’t undo tissue damage that’s already occurred, but it can stop it from spreading. Some dogs need more than one vial, depending on the severity of the bite and their response.

The vet warned me that even after treatment, complications can still arise:

Delayed bleeding

Swelling that impairs breathing

Tissue death near the bite site

Infection

And in rare cases, organ damage or clotting disorders that emerge hours later

That’s why they kept Ziggy overnight, and why it’s so important to have your dog monitored closely for at least 24 hours post-bite.

Advice to other dog owners

Know where your emergency vet is before you need it

Act fast, even if your dog seems fine at first

Don’t assume weather makes you safe from snakes

Get educated and prepare as best you can—but don’t beat yourself up when nature surprises you

I’ll update once we’re past the 48-hour mark. But I already know I want to thank the vet staff in both Los Alamos and Santa Fe who treated Ziggy like their own dog. And I want other hikers to know: snakes don’t care what the weather is. Be ready anyway.

Have you been through a snakebite or other animal emergency? What helped? What do you wish you’d known earlier?

I wouldn’t waste time with the vaccine. The manufacturers claim that it gives you extra time to get to the vet. Join the National Snakebites Support group on Facebook to learn the truth of why the vaccine isn’t recommended. In short, there isn’t any scientific evidence to back up the claims made by the manufacturer.

I’ve had two dogs bitten by rattlesnakes. Bites are largely survivable, even without antivenin. I know how terrifying it is when your dog is bitten.

Rattlesnake avoidance training is absolutely the way to go, IMO. The trainer you use makes all the difference. The trick is finding a company that treats both the dogs and the snakes they use humanely and ethically. I know of a great company that comes to NM yearly.

I have 5 dogs. All 5 have had training and re-tests years later. I’m happy to report that all of my dogs remembered their initial training and passed with flying colors. And yes, I have a couple of dogs that qualify as nervous. Again, the quality of the trainer makes a difference. There’s only one company I would trust for this type of training. They were patient and gentle with all of our dogs, including the nervous/anxious ones. I even have some of their trainings on video.

Dogs don’t learn their lesson after being bitten by a snake. The best defense is teaching them how to avoid venomous snakes.

Thanks for the informative post. I had no idea there was a rattlesnake venom vaccine. I'm fascinated that's even possible. Our dog has a really strong prey drive (or play drive, when it's other dogs). I've been worried about rattlesnake run-ins (and coyote run-ins, due to the latter) since we moved here.

You mentioned rattlesnake aversion training, which we did when we first moved here. I don't know if the training "took." Our dog was traumatized by even a mild shock and wouldn't go near the training area after the first mild zap. Conversely, there was another dog there that was deemed untrainable because it didn't respond to the shocks at the highest level.

It's been five years since we did it, we haven't seen a snake and/or he's avoided them. so I've been unsure what would happen if we actually encountered one. As I don't think putting him through the training again makes sense, and being out on the trails sniffing at every bush is one of his favorite things in the world, it's helpful to read this advice and have a plan in case he does try to make the wrong kind of friend.