Dedicated low-income housing: Or, how we subsidize housing for people who need it

Plus, how regular-degular housing can stop displacement and keep a town affordable

Whenever a new housing development is proposed in Los Alamos, the same question reliably comes up at our planning commission meetings (or social media): “What percentage of these apartments will be affordable?”

It’s a reasonable question! Residents want homes that teachers, firefighters, plumbers, and young families can afford. But the question reflects a common misunderstanding of how affordability works—and how it doesn’t.

The basics: Affordability has to pencil out

“Affordable” technically means housing costs no more than 30% of a household’s gross income. But where does affordability come from? Not from developers having charitable feelings. If it costs $400,000 to build each unit—including land, labor, materials, financing, and fees—rents or sales must cover those costs. Otherwise, the project won’t happen.

Imagine a baker. She could sell her loaves for a penny because she’s a nice person who feels generous. Or, she could be very greedy and demand $100 per loaf. But she can’t do either for long without going out of business. So it is with homebuilders. In Los Alamos, construction and labor costs are at an all-time high. Builders are already squeezing profit margins and pushing hard against what renters and buyers can afford. When you see expensive new housing units sitting empty for a long time, you’re looking at builder costs that have been T-boned by buyer price ceilings. Builders, like bakers, have a strong incentive to lower the cost to where people will actually buy their products.

If they aren’t lowering prices, it’s probably because they spent way more money than they expected to get those units built, and/or buyers have a lower price ceiling than expected. The math ain’t mathin’.

You can’t guilt the capitalism away

Many people assume high rents or home prices are purely about greed*. From this, they argue that public pressure can shame developers into giving up on profit and offering below-market rents or homes. Some even demand that 30%, 50%, or 100% of units be officially “affordable.”

Sometimes, that’s just stealth NIMBYism. A few residents use unrealistic affordability demands to block projects entirely. It’s a clever tactic: sound generous while ensuring nothing gets built!

But in my experience behind the dais, most people asking questions about affordability are sincere. They truly want homes for working families—they just don’t understand how affordability happens or why it’s so scarce in Los Alamos.

How homes become affordable in the real world

There’s a common expectation that “affordable housing” will come from brand-new construction that has been made, somehow, affordable. People get angry at expensive market-rate housing (especially apartments, because people have feelings about those in general) going up in a way they never get mad about decrepit houses selling for nearly the same. This is curious. Normally in the world, newer things are more expensive than older things. New housing construction is especially expensive. New homes rent or sell at the upper end of the market because of high land costs, building materials, labor shortages, zoning restrictions, and stringent building codes.

So where does affordability come from? Two places, neither working especially well at the moment:

Subsidies: Also known as Capital-A Affordable Housing. Someone (usually government) covers the gap between what it costs to build and what lower-income residents can pay. Programs like Section 8 (demand side) and LIHTC (Low-Income Housing Tax Credits) or USDA Rural Housing (supply side) do this. We need subsidies! But subsidized housing in the U.S. is costly, limited in scale, made illegal by most zoning, and often plagued by maintenance problems. All of this is a policy choice, by the way—not a law of nature: Other countries do it better.

Filtering: Older housing becomes more affordable over time as higher-earning renters and buyers move into newer units. Today’s “luxury” apartments become tomorrow’s middle-income housing—if there’s enough supply. In Los Alamos, chronic undersupply has broken the filtering process. Even 1950s quads with orange shag carpet and leaky roofs now sell for $500,000. Why? Too few homes. Too many bidders. Scarcity, not quality, ends up driving prices.

Inclusionary zoning: a feel-good policy that can backfire

One popular idea is to force developers to include affordable units in new projects—a policy called inclusionary zoning (IZ). When people ask, “How many of these units will be affordable?” this is likely the policy they have in mind. We do not have IZ on the books in Los Alamos, but periodically, someone will suggest it. I get why: It sounds great and is politically appealing! But it often fails in practice. Most people assume that the homebuilders themselves will subsidize the cheaper units. They do not. They pass the cost on to other tenants or just avoid your town altogether. Santa Fe tried a version of IZ that caused a near-total construction halt, driving up prices for everyone and hurting the very people it aimed to help.

Demanding builders subsidize the cost of below-market units is like telling our baker to sell 20% of her loaves for $1 while flour costs soar and workers are scarce. She’ll either move her bakery to a town without that rule, or hike prices on everyone else’s bread to cover the losses.

If Los Alamos really wants to do IZ, there are ways! Some cities have been able to secure affordable units by applying IZ carefully, often limiting it to ownership housing, where it’s more feasible, or offering real incentives to offset costs. Just keep in mind that if a developer can walk away, whatever stick-it-to-the-man rules you lay down can be counterproductive. It’s hard to get homebuilders interested in Los Alamos to begin with—if your rules drive them away, you’re hurting people who need that housing.

Affordability has to be incentivized, not imposed in ways that kill projects.

My policy philosophy in one line: Avoid policies that sound good on paper but hurt people in practice—especially the people you’re trying to help. Wait until I get to parking mandates!

The real solution: Build more (yes, including market-rate housing)

If we want more affordable housing, we must start by building more regular housing.

That includes new market-rate apartments, condos, and townhomes that higher-earning households will rent or buy, so they stop competing for older, lower-cost homes. Think of new housing, even the upsettingly-pricey kind, as a sort of “yuppie containment strategy.” Without it, the dual-income PhD couple sails into town and bids up every shabby 1960s rancher, pushing your dry cleaners and daycare-workers and nurses off the Hill and nudging your housing prices higher and higher. Displacement happens not because we build too many homes, but because we build too few.

The filtering principle applies to the auto industry: We don’t force automakers to sell new cars at low prices. Higher-earning buyers purchase new vehicles, and the rest of us buy older, more affordable ones. The same should happen with housing—if supply is allowed to grow.

And no, it’s not true that new market-rate housing inevitably causes gentrification. In constrained markets, adding new units reduces displacement by relieving pressure on existing housing stock.

A policy choice—and one we can reverse

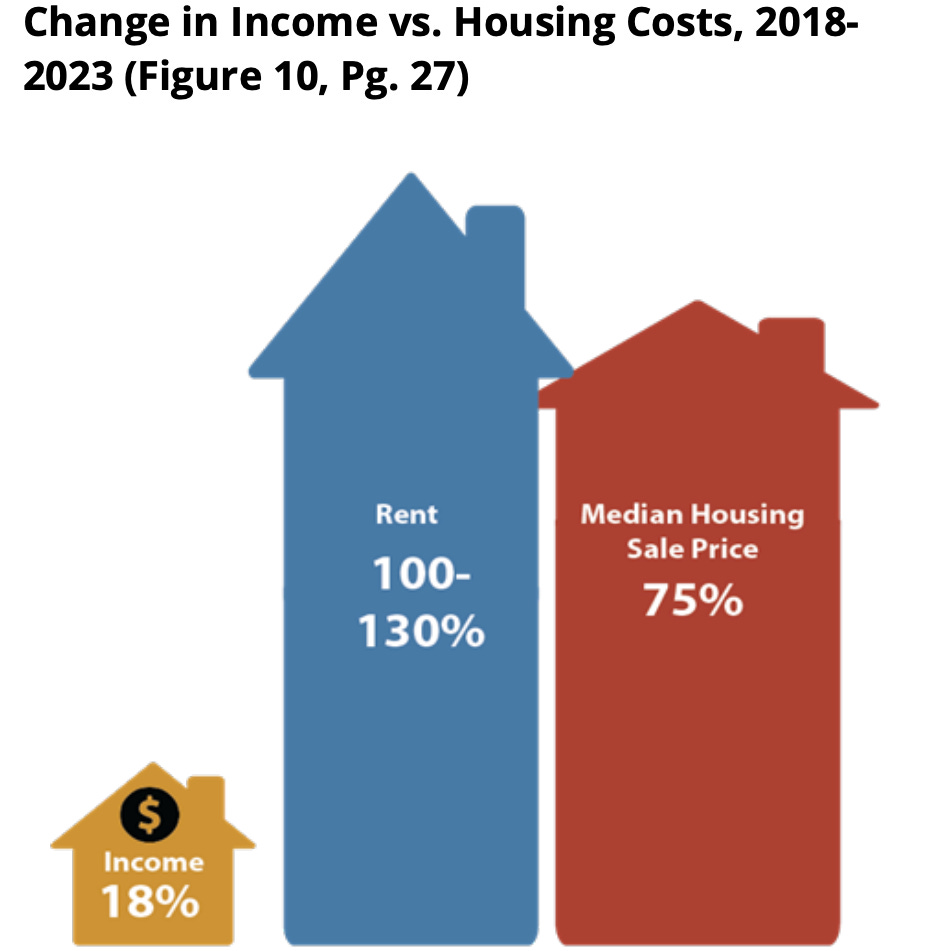

Our housing scarcity is not an accident or an act of nature. It’s the result of decades of policy decisions—choices repeated across the country and especially hitting Los Alamos and all of New Mexico hard right now.

Affordability is a choice. And we can choose differently.

If we want our town to remain a place for everyone, not just for senior scientists but for teachers, EMTs, lab techs, and young families, we need to stop doing things that don’t work. We need to be outcome-oriented, not process-oriented. We need to be practical, not ideological. We need to allow housing supply to catch up with demand, let filtering do its job, and do a better job of getting subsidies to those who need them.

Otherwise, we’ll keep driving up prices and wondering why the affordable housing we demand never seems to appear.

Great article! Very well thought out.

High property taxes keep many people in the same homes. I am not moving and tripling ( or worse) my property taxes…..therefore the supply of older homes is somewhat frozen. If the goal is to increase the supply of homes and have people move up to newer or bigger homes taxing the activity of ownership higher and higher works against that. Tax and regulation cannot be excessive or the activity is suffocated.