‘But seriously, where will I park?’—addressing real concerns

Part 2 on parking reform in northern New Mexico

This is the second of two articles (really, one long article chopped in half) on parking reform in northern New Mexico. In Part 1, I showed how parking mandates force developers to build expensive car storage instead of housing. In Los Alamos, we can see that while residents report high levels of satisfaction with the supply of parking, only 7% think affordable housing is adequate. There is a connection between these two: more parking means less housing choice and more expensive housing. Here, I explore how we got here and what bolder action could achieve.

How we created this problem

Starting around the 1950s, parking mandates spread across the country, forcing car dependency and transforming previously green, pleasant places into asphalt jungles. Walk (don’t drive) through downtown Los Alamos, Santa Fe, Española, or Taos and you’ll see the evidence: dirty, lifeless oceans of pavement that sit mostly empty, choking our town centers.

Becoming a planning commissioner really taught me how weird it is that the government ever got involved in parking. As I wrote before, it’s as if cars could vote—everything revolves around them. If housing is a human right, why is it parking that we mandate? Is that really where our values lie?

When parking last came before the commission in 2023, I had the following exchange with our planning manager:

Chair: Are there any other questions from commissioners for county staff or DPS?

Me: This is a question for [Planning Manager] Sobia, because it’s in the staff report. It says parking is a regulatory tool by which the CDD can direct the type and intensity of desired growth. And the way I read that, and correct me if I’m wrong, is that it’s sort of like a lever; you can use increased or decreased parking to direct growth. So anytime you mandate more parking, you are always going to reduce growth. Housing will be more expensive, you will have less growth.

Planning manager: That is correct.

Me: Thank you.

In other words: Parking mandates are not just about cars, they’re about growth and housing. While I think planners in general could explain the consequences of our land-use rules better, the buck stops with elected leaders—so ultimately, this is on them, and they can fix it. They can take all this complicated mess and make it very simple and very clean.

The induced driving trap

More parking creates more driving, which creates more traffic—the opposite of what communities want. The induced-driving effect is well documented. Just as highways fill with traffic as soon as they’re built, free and abundant parking encourages car trips that wouldn’t otherwise happen. (If you’re skeptical, please read this nerdy piece for more.)

Walkable places need population density to support protected bike lanes and frequent transit. People won’t take the bus if it’s not coming frequently enough, and the bus won’t come frequently enough if too few people are taking it: You solve this dilemma by welcoming more neighbors to your town and letting housing be built closer together, especially near bus stops. (I wrote here about how we can do this in Los Alamos.) When we mandate dispersed development surrounded by oceans of parking lots, we make this virtuous cycle impossible. We lock ourselves into a pattern where driving becomes the only practical option, then justify more parking because “everyone drives.”

Parking lots are fiscal losers compared to vibrant, alive buildings that house businesses and residents. Asphalt generates minimal tax revenue while requiring the same infrastructure investments—roads, utilities, snow removal. If you’re an elected leader who is serious about fiscal responsibility and better land use, eliminating parking mandates is one of the most cost-effective reforms available. It is a simple, clean, and effective tool that can be implemented quickly. Why not introduce an ordinance at the next meeting to clean up your city’s land-use code with this reform? There is probably no other single policy change you can do to help your city more—and at no cost to the taxpayer.

You can’t love parking and love the environment

Well, you can love both. But you can’t have both. Residents who are driving EVs, giving up meat, electrifying their houses, and urging solar panels on every rooftop should add “eliminate parking mandates” to their climate advocacy toolbox. Every mandated parking space is a vote for more driving, a hotter planet, more forest-chewing sprawl, and more emissions spewed into our air and our kids’ lungs.

That’s right: parking lots aren’t just ugly—they're environmental disasters. Asphalt absorbs heat, creating urban heat islands that make summers more sweltering. Storm water races off these impervious surfaces, picking up oil, antifreeze, and tire particles before dumping polluted water into our mountain watersheds. Our fragile high-desert ecosystem wasn’t designed to handle this kind of nasty runoff.

But the real damage happens at scale. When we force housing into car-dependent sprawl patterns, we lock in decades of greenhouse gas emissions. You can tell yourself that your kid’s teacher is commuting from Española to Los Alamos every day out of choice rather than necessity, but how to explain why there are so many more commuters overall? Watch those 10,000 drivers wearily climbing the hill any given morning to get to work and think to yourself: If those people could live closer to their jobs, how much carbon could we save? (Not to mention lives.)

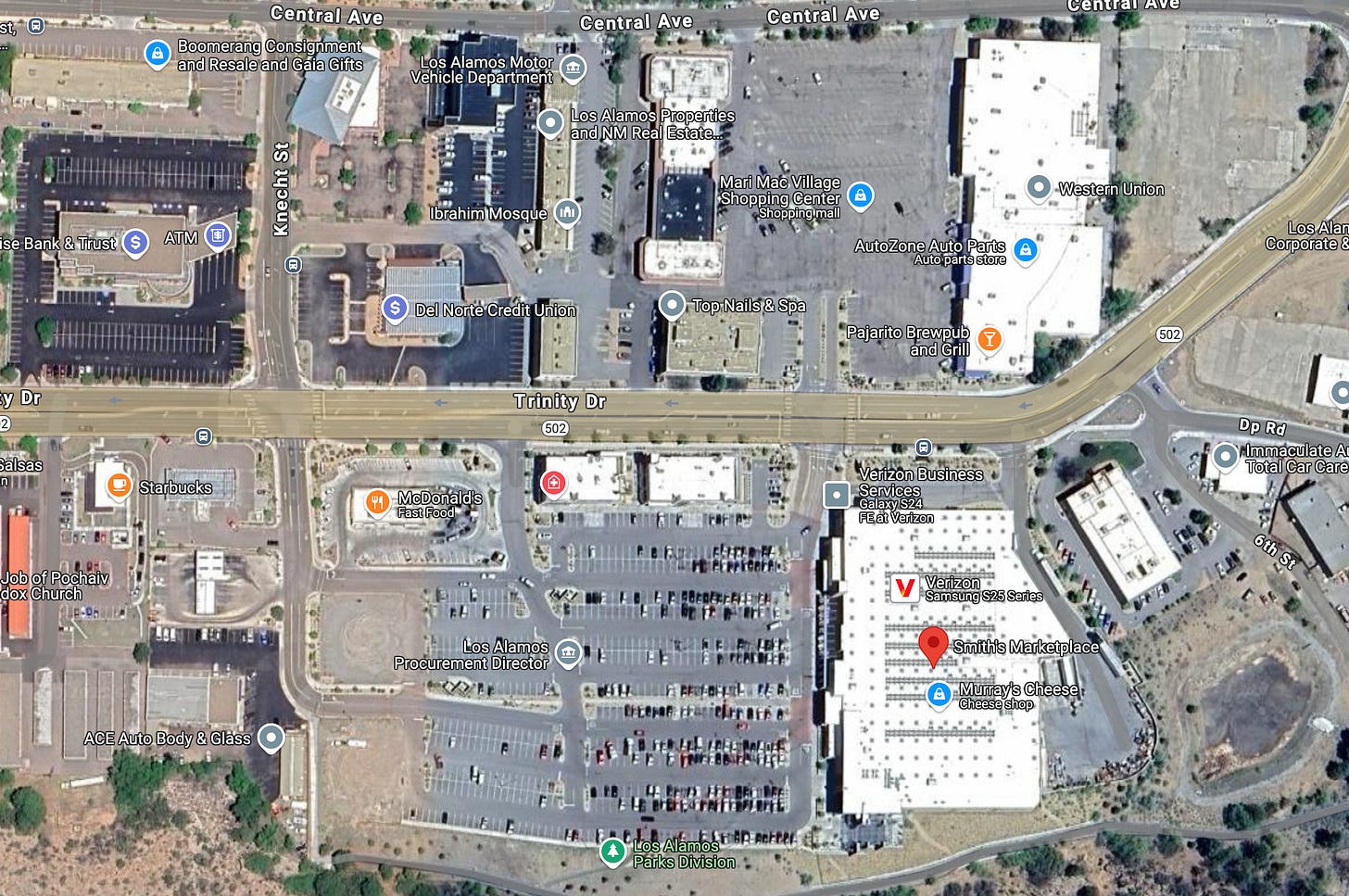

If thousands of housing units appeared in Los Alamos overnight, does anyone really think they’d sit empty because people just love commuting so much? Of course not. The demand is there, it’s always been there. Exclusionary, land-gobbling policies like parking mandates are what’s in the way: Look at the satellite photo at the top of this piece and tell me “we’re out of room for housing” with a straight face. These are policies we chose, and we have the power to change.

If we want to do our part to reduce emissions in our region, then we must stop mandating the infrastructure that makes driving the only viable option. You can’t pave your way to sustainability.

Learning from success stories

Parking reform is not a fad, nor the fever dream of a few radicalized urbanists. It’s recommended by organizations as varied as AARP, the American Planning Association, Strong Towns, the Southern Environmental Law Center, Climate Changemakers, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, the Yale School of the Environment, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Housing Affordability Institute, and the US Department of Transportation’s Climate Change Center (which has somehow survived DOGE). Hardly radical organizations, these are mainstream voices concerned about housing affordability and sustainable development.

Montana—a rural mountain state full of communities similar to ours—recently passed a major parking-reform bill aimed at housing affordability. When Auburn, Maine (population 24,000) eliminated parking mandates, new restaurants opened immediately in existing buildings. Buffalo eliminated mandates in 2017 and not only has the sky not fallen, the city blossomed.

When people tell me (and they do, frequently), “parking reform is fine for big cities but we’re a small town,” I tell them that smaller communities have been at the forefront of removing parking mandates. When Ecorse, Michigan (pop. 8,941) eliminated mandates, a former ice cream shop became a Puerto Rican restaurant without the owner having to worry about creating additional parking spaces that would have killed the project’s economics. “Speed of development review is so much faster,” said a planner from Ecorse. “That’s true for developers and for city staff. Parking just takes so much time and energy from everybody involved.” Brave leaders in town after town are seeing the light and making real decisions that help their struggling constituents.

Tools (other than mandates) to manage parking issues

Nobody wants to circle downtown looking for a space or to deal with neighbors complaining about spillover parking. But eliminating mandates ≠ eliminating parking management. Since parking reform has been around for a bit, cities have developed proven toolkits for dealing with these concerns as they arise:

For peak events (like summer concerts): Park-and-ride shuttles work better than asphalting large chunks of precious real estate for a few days of intensive use per year. Just as you don’t build your house around your big annual Christmas party (“I’d like 5 living rooms and 10 bathrooms, please”), you don’t build your town around Black Friday shopping.

For neighborhood spillover: Residential permit programs like Tucson’s protect neighborhoods without forcing developers to overbuild. More on spillover management here.

For business districts: Dynamic pricing and time limits in high-demand areas ensure turnover while developers still build what customers actually need. (More on the business case for reforming parking here.)

For local reinvestment: Parking benefit districts channel meter and permit revenue back into neighborhood improvements—sidewalks, bike infrastructure, transit connections. Austin’s West Campus residents who initially opposed paid parking now love the improvements their meter money funded.

For modern management: App-based payment systems eliminate hardware costs and enable instant price adjustments. São Paulo saw 60% revenue increases by replacing coupons with mobile payments, while sensors help drivers find spaces without circling.

Over-supply from mandates often creates worse parking problems by encouraging unnecessary trips. To combat this, Ventura County implemented a “parking benefit district” in 2010. By 2013, 83% of business owners ended up supporting it. As the business association director said: “Our merchants have come to appreciate that their customers can usually find a stall in front or near their store for little more than a dime or a quarter.”

Builders have skin in the game: if they guess wrong on parking, it comes out of their bottom line. Parking mandates replace this incentive structure with arbitrary and capricious requirements that impose costs on the wrong people…the public.

Northern New Mexico’s leadership opportunity

According to Los Alamos’ 2024 Affordable Housing Plan, we need 1,300-2,400 units by 2029 just to arrest spiraling housing costs. At our current pace of only 62 units annually permitted, it will take 21-39 years to meet the identified need.

Right now, Los Alamos is dumping its problem onto our neighbors, immiserating countless workers to lock in privilege and comfort for a few. Santa Fe1 is doing something similar, prioritizing nostalgia over livability to appease wealthy incumbent homeowners and rake in those tourist dollars—all while displacing families who’ve been in Santa Fe for decades or even centuries.

Regional coordination across Santa Fe, Española, Los Alamos, and Taos could stop any one community from creating externalities that harm others. By developing a coordinated transportation and housing plan (which would include, of course, ending parking mandates), we could create a model for other mountain areas. We could protect what really makes northern New Mexico special—its people. Not low-rise brown buildings. Not convenient free parking. Not seas of hot asphalt and half-empty strip malls. We have the chance to show that mountain communities can lead on progressive policy that works in practice.

This isn’t about eliminating parking. The places that have eliminated mandates still have parking spots. It’s about eliminating rigid, one-size-fits-all rules that prevent us from building the kind of communities we say we want. Developers will still build parking—they just won’t be forced to overbuild it based on outdated formulas that vary arbitrarily from town to town.

If current rules aren’t getting results, it’s OK to do something different

Los Alamos residents have spoken clearly in community surveys: They want housing solutions and downtown vitality. Parking mandates deliver neither. We’ve tried the status quo—abundant parking but empty, depressing downtowns; easy car storage but a housing crisis that forces more and more of us to commute from other counties.

Montana leaders showed courage and took the leap. Small towns everywhere are showing it can be done. Northern New Mexico has the opportunity to demonstrate that mountain communities can row together to lead on sensible policy that works in practice to increase housing affordability, economic vitality, and climate resilience—we just need some political courage to make it happen.

To learn more about parking and Santa Fe, watch author Henry Grabar’s Livability in the Land of Enchantment talk, here. To learn more about how Santa Fe’s building codes affect affordability, watch local author Chris Wilson’s Livability talk, here.