This is the final entry in my virtual book club to discuss

’s Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity. Each week, I have been diving into one chapter, connecting the national story to what I see locally. Join me in the comments with your own observations about mobility, housing, and community in your area. This week: Chapter 10, “Building a Way Out.”Previous chapter discussion here.

The three principles of reform

After nine chapters diagnosing how we got here, Appelbaum finally offers his prescription for how to get out of this mess: If America wants to regain its dynamism, we need a framework built on tolerance, consistency, and abundance. No one principle can stand alone. Tolerance without consistent rules leads to anarchy; rules without tolerance calcify into exclusion; abundance without the other two only invites backlash. Let’s dig into these principles in turn:

Tolerance: embracing messy diversity

Organic growth is messy and unpredictable. Giving Americans the freedom to live where they want requires tolerating the choices made by others, even if we think the buildings they erect are tasteless, or the apartments too small, or the duplexes out of place.

We got here, to an America segregated by income and race, because intolerance was codified into zoning. We probably can’t pluck intolerance from the human heart, but we can un-codify it. We can rewrite the rules to allow for variety—casitas, triplexes, and boarding houses in every neighborhood. Over the 20th century, America “slowly purged from our landscape most forms of genuinely affordable housing,” Appelbaum writes, cloaking exclusion in the language of safety and order.

The most intolerant bloc has always been incumbent homeowners. They are the primary veto point—the “privileged and propertied” of Appelbaum’s subtitle. Many feel entitled not just to their own backyard, but to everything within a five-mile radius. As one person put it to me in an off-the-record discussion about housing: “When I bought my house, I bought it on the assumption that zoning guaranteed nothing in my neighborhood would change.” And she was right, in a sense, because zoning promised her exactly that.

Elected representatives, exquisitely attuned to those who attend Tuesday night hearings, reinforce this intolerance. Studies show older, whiter, wealthier residents overwhelmingly dominate housing meetings—and they vote. So politicians defer to them. The result: new housing is hellishly difficult to build and usually relegated to the fringes. Once American-style zoning takes over, a town is frozen in amber: everything in its place, in tidy little rows.

Appelbaum calls this the “fatal hubris of zoning”—the arrogant belief that officials in a room can centrally plan the perfect city, which will then never change. I think Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns would agree that humility is the missing ingredient. When top-down rules codify intolerance, they become weapons of mass exclusion.

Tolerance means restoring the humbler rungs of the housing ladder. Reformers once pathologized boarding houses and immigrant tenements as unsanitary or immoral, as if the buildings were the problem rather than the poverty of those they housed. However, those units, imperfect as they were, generally served as stepping stones to stability. Nobody is arguing for the return of overcrowded and unsafe tenement conditions. Nobody is arguing that an apartment is ideal for everyone. Appelbaum does argue, however, that we need to reintroduce a sufficiently diverse stock of housing to service a variety of human conditions: not all those seeking housing are 40-year-old professionals with 2.5 kids, 2 cars, and a Labradoodle.

Housing needs shift across a lifetime as well. How many elderly adults are trapped in rambling houses, unable to drive, dependent on younger friends for rides? The AARP knows this, and calls for re-legalizing variety: apartments (including micro-units and co-living arrangements), duplexes and fourplexes, rowhomes—and of course, the classic granny flat. These are the forms we’ve zoned out of existence—even though (or because) they keep shelter affordable.

Consistency: clear rules, not case-by-case politics

The second principle, consistency, means creating clear rules that allow development “by right.” That means if a project meets the code, it gets approved—full stop. No further hearings or debates.

“Rules work best when they apply uniformly and predictably over the widest possible geographic areas,” writes Appelbaum. That sounds obvious, but it’s not how our system works today. Even projects that follow the rules to the letter get dragged through hearings, appeals, and neighbor vetoes.

On paper, project-by-project hearings might look like democracy in action—more participation must be better, right? But when you push participation to the tail end of the process, after an owner has already sunk money into land purchases and project design, you’re not empowering the public—you’re empowering veto players. That procedural burden delays projects and introduces uncertainty about timelines and ultimate success, which results in significant costs that are passed on to renters and homebuyers. It also skews decision-making toward those with the time and resources to show up and then, on many occasions, follow up with lawsuits. In practice, this is a system heavily tilted toward incumbent homeowners—not renters, not commuters, and not future residents.

Appelbaum argues that a more democratic approach would move decisions to the front end—where rules are written, debated, and voted on. That’s when the whole community can weigh in. If the rules are clear and predictable, everyone plays by them fairly. If they aren’t, each project becomes a political football.

We’ve seen this play out locally. A friend shared this newspaper clipping from 1982 showing how our county’s Planning and Zoning Commission approved a rezone to allow a modest 3.5-units-per-acre project—hardly “high density”—only for County Council to overturn it. Why? Because twenty neighbors showed up to complain. One councilor declared that rezoning to allow infill density was “the wrong way” to build, insisting that any new homes should go out in the fragile canyons and forests nearby: “We need Rendija Canyon,” he said. Another councilor was simply in denial: “I don’t see a need,” she said. It wasn’t just these individuals, the County Council of 1982, or even this community. Year after year, decade after decade, town after town, this mindset has remained: No to density, yes to sprawl.

When development isn’t permitted by right, those outcomes are inevitable. The ladder gets pulled up, forests get paved, and the most vulnerable always lose.

Abundance: enough homes for everyone

The third principle is abundance: building enough housing that everyone has a seat when the music stops. This would make for a very boring game of musical chairs, but it would certainly be an improvement on our current “game,” which often leads to homelessness. “We need to turn housing from a scarce asset back into an abundant resource, from an appreciating investment back into a consumer good,” writes Appelbaum. He cites estimates of 30 million new units needed in the next decade, which would require us to double our current pace of building.

But abundance isn’t just about numbers. It matters where those units go. Building thousands of homes in a field in Nebraska won’t solve a mobility crisis. Housing needs to be built as close as possible to good work, good schools, and opportunities. If you shove all new housing into low-opportunity areas, you create traps.

This chapter shows the strongest alignment between Appelbaum and today’s “abundance agenda,” the policy framework that argues we need to build and produce more of what we need, from housing to clean energy to infrastructure. But housing experts disagree on both the scale of the shortage and the pace of the solution. Kevin Erdmann has argued that the US is about 20 million units short—far more than most estimates—primarily because post-subprime lending restrictions went too far. Yes, some credit tightening was clearly needed, but Erdmann argues that the crackdown was too broad, pushing creditworthy buyers into permanent renting and eliminating the sub-$250k home market that once provided starter housing.

For his part, Chuck Marohn argues that the abundance approach faces a structural problem. He agrees with Appelbaum that housing has transformed from a shelter that gently appreciated into a stock market that you live inside—but given how much the economy now depends on real estate values, Marohn worries that flooding the market with housing could trigger a broader economic collapse. The Strong Towns approach advocates for small-scale, incremental change: sprinkling housing into the market instead of pouring it.

There are many approaches to addressing the supply problem,1 but most affordability advocates agree that supply is a significant issue. And they agree that the economic stakes are staggering. Economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate that housing constraints in high-productivity cities have cost the average American worker (that’s you and me) $8,775 annually by preventing people from moving to places where their labor would be most productive. “It’s a rough estimate,” writes Appelbaum, “but it gives a sense of the scale of the distortions we have introduced and the price we are each paying for them.”

Preservation, or petrification?

Appelbaum also skewers the way historic preservation has been weaponized. What began as an effort to save landmarks now designates even parking lots as “historic.” Charleston is his case study: once a major American city, it mummified itself into a tourist destination by refusing growth. “What remained was not the city as it ever was, but the city as its white elites clearly wished it had always been,” writes Appelbaum.

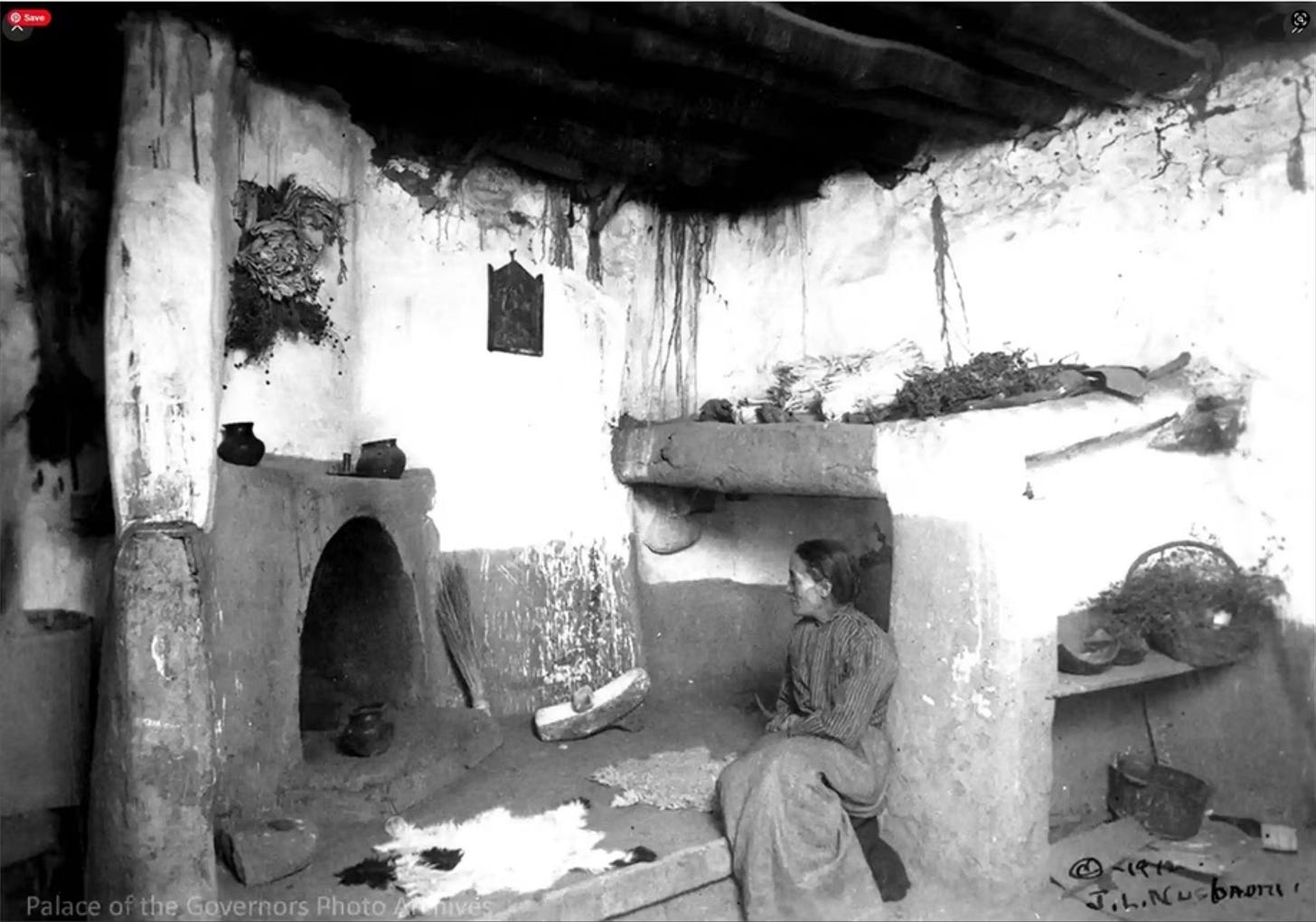

Santa Fe is our local parallel. Like Charleston’s preservationists, who pushed the costs of their vision onto vulnerable populations, Santa Fe’s strict preservation laws have created similar displacement patterns. The city’s 2021 “Historic Districts Handbook” documented significant demographic shifts: while Santa Fe’s overall population grew by 69% from 1980 to 2018, the historic districts actually lost population—a 26% decline—most of it among the Hispanic population whose ancestors built that housing.

Santa Fe likes to call itself “the City Different,” but in preserving its façade for moneyed visitors, it has lost much of its actual uniqueness: The report found that “the historic districts have gotten whiter and less Latino over the study period,” with census maps showing substantial declines in Latino population share across most historic district areas. One resident quoted in the report observed: “Dad would say all the Hispanics are going to move and the only thing that will remain is the Spanish street names, and that has come to be.”

The Santa Fe pattern mirrors Charleston’s use of preservation to create a sort of theme park, rather than a place where regular people live. Historic preservation expert Chris Wilson, speaking at a 2024 Livability talk in Santa Fe, acknowledged that preservation “is often a catalyst and a contributor to gentrification.” Yet, the community’s “strong commitment to a vision of Santa Fe that’s two story” means that housing solutions can only happen at the edges—creating car-dependent sprawl and further displacement of locals.

Do cities want to be museums for tourists or living, breathing communities? And who really benefits from preservation movements—whether in Charleston or Santa Fe—that systematically exclude the very people who created these cities’ authentic character?

Reforming the rules that broke mobility

Appelbaum closes by laying out a choice: If we continue to rely on markets to provide housing, we must stop choking them with stifling regulations that produce only luxury housing. If, on the other hand, we want a massive investment in public housing, we must elect different people and commit to the taxes that would be required. Regardless, zoning has to change. Even if the U.S. were to pivot tomorrow to a Viennese-style social-housing system (which seems unlikely!), most of it would still be illegal—remember that most residential land in America is reserved for detached single-family homes on large lots. You can’t build a public-housing complex there—or even a few deed-restricted townhomes.

Appelbaum says that we are currently in the worst of all possible worlds: banning affordable housing types while failing to build alternatives. If we keep this up, he writes, we compound “malignant indifference with overt cruelty.”

The consequences are everywhere: unaffordable housing, long commutes, young people unable to start families, wildlife habitats destroyed, a hobbled economy, soaring greenhouse-gas emissions, and rising traffic fatalities. We have built ourselves into a corner, where we remain … stuck.

Do we still believe in mobility?

Appelbaum concludes by wondering if America’s mobility was merely an adorable phase of our country’s chubby-faced youth, now long behind us. Have we hardened into the inherited castes of place and identity that we see in other, less dynamic, less free parts of the world?

For two centuries, Americans have believed in mobility—not just geographic, but also social, economic, and civic. We believed that where you start isn’t where you have to end. If enough people still believe in mobility, the path forward is clear: tolerance, consistency, and abundance. Build enough housing, in the right places, under fair rules.

Nothing less will restart the engine of American opportunity.

Next week: Yes, we’re not quite done! I’ll post a denouement of this chapter-by-chapter experiment—plus your Chapter 10 reader comments.

Reader comments from Chapter 9:

Andy Boenau of Urbanism Speakeasy: “To this day, environmental laws are a go-to NIMBY weapon.”

Galen Rosenberg shared his personal experience with California’s highly unequal Proposition 13, saying he’s paid the same property taxes since 1987 while his new neighbors pay ten times more for identical services.

bnjd from What Are Streets For Newsletter defended localism: “We localists need to conceive of methods for implementing good localism and preventing bad localism.”

Charles Thomas of City Anatomy argued that mobility has painful downsides, noting that frequent moves harm children’s school performance and social networks.

Eduardo Santiago challenged the framing of declining fertility rates as problematic rather than beneficial.

Discussion questions for Chapter 10:

Appelbaum argues that affordable housing programs often trap people in place rather than enabling mobility—do you see this dynamic in your community?

Should historic preservation take priority over housing abundance, or can cities balance both goals effectively?

What would “growing the pie” rather than redistributing scarce housing look like in your area?

Here are some exciting ideas at the federal level that tackle the regulatory, financing, and technical barriers to housing abundance.

In Santa Fe and Los Alamos, what I can’t get my head around is how we balance the need for housing with the water limitations. Do you have thoughts on that?

I missed last week's discussion as life has gotten in the way but I am so happy to be finishing this book out with you!

Chuck Marohn was in KC last week and I went to his talk. There were so many Strong Towns-ish ideas in this final chapter, and a big one is the tension between housing-as-shelter and housing-as-financial-instrument. Chuck spent a good amount of his talk on this, and Applebaum mentions it as well. This could be (and I'm sure is) its own book-length topic. I don't know how we make that transition given how many boomers are relying on their home values as their nest egg for retirement, which many are at or reaching in the next 5-10 years. As much as I love the idea of returning to a world where housing is a consumer good, it does strike me that people my age (Millennial) have already lost out on the investment vehicle of pensions enjoyed by prior generations, plus our social security won't be fully funded, and now we aren't to have real estate as an option either? The housing theory of everything strikes again - it'll be a complex needle to thread so that people do in fact end up better off if/when we build so much that the cost of housing falls significantly.

There was a lot in this chapter that ties in with ideas in the zeitgeist (hello, abundance) and also personal things my husband and I have been weighing as we have been looking at houses this month (and also considering whether we wouldn't prefer building a small ADU on our current lot instead). I think I'll save some of those thoughts for your wrap up.

But just one other thing that Applebaum lightly touches on in this chapter that has interested me throughout the book. He considers whether the generations of mobility were the exception and that our current stasis is a permanent return to a way of life where people, for the most part, stay near where they were born. I think this may be the case, because of how different our economic situation is compared with the economies of the late 1800s, mid-century, and late-20th century. For one thing, healthcare is an enormous part of our economy. It's like, that and the AI speculation propping us up right now. Healthcare jobs are decent, but they're not super dynamic. And they're scattered throughout the country. Someone wanting to become a doctor or nurse may need to move to their next biggest town over, but they don't need to switch states or in many cases even the county they live in. As for the other jobs Applebaum mentions that are still a draw to the big cities - they're in tech, financing, law, and consulting. These aren't jobs that you can show up and do if you have some basic skills and a solid work ethic, like the factory jobs in Flint, or the farmstead life from an earlier generation. These are jobs moated by years of very expensive education. I just keep coming back to the idea that it's really economic mobility that matters here, and that in the future it's probably still the jobs at the very top of the food chain that will require people to move to certain giant cities, but that for the rest of us it's about finding abundance where we are already.