Why ‘just build more treatment centers’ isn’t enough

Part 2 of a 4-part series on homelessness in northern New Mexico

When Santa Fe County Commissioner Justin Greene recently proposed a comprehensive “campus model” for addressing homelessness (centralizing shelter, services, and treatment in one facility) he touched on a common belief: If we could just treat the visible symptoms we associate with homelessness—mental illness, addiction, unemployment—we could solve the crisis.

“People become unsheltered in many ways—job loss, trauma, economic pressure, mental illness and substance abuse are just a few,” he wrote. “These are also the starting points for reversing course. By addressing the causes, we can create pathways for people to regain independence and stability.”

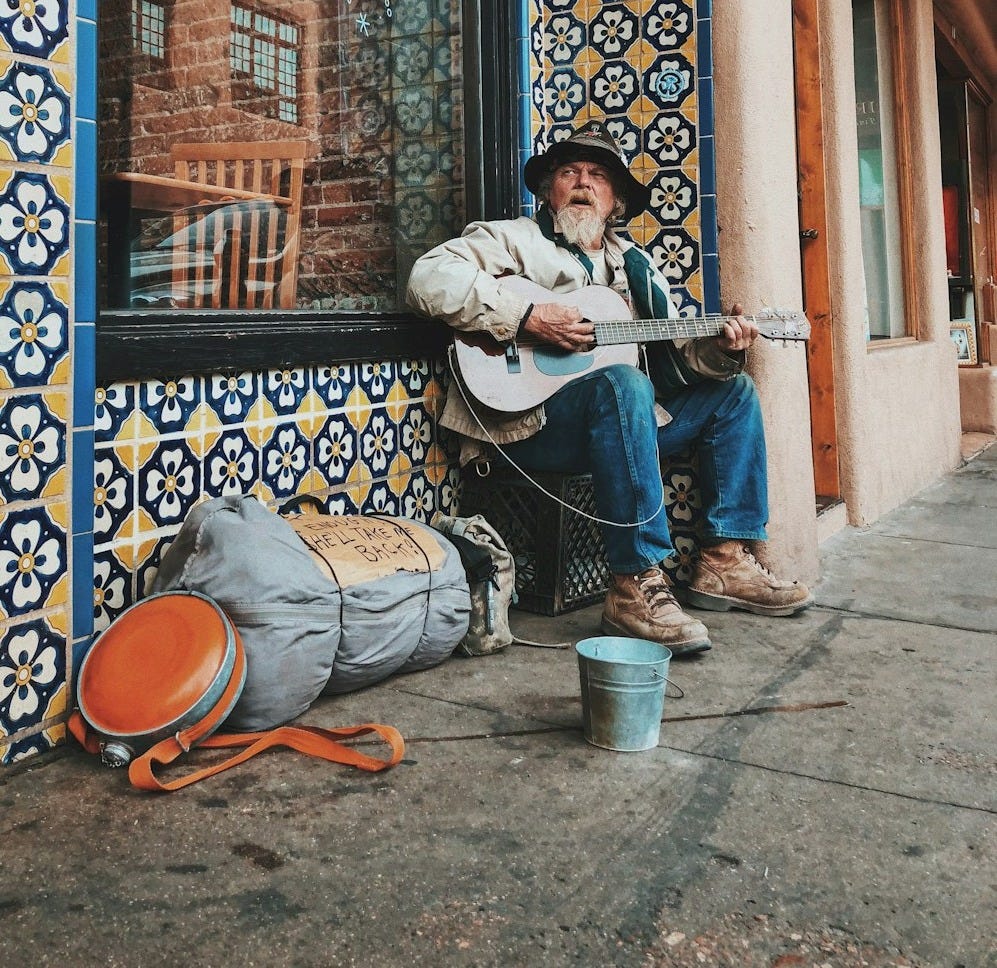

It’s an appealing idea! Many people we see struggling on Cerrillos Road or in encampments along the river do struggle with mental illness or substance use. Treating those problems seems like a logical solution, offering hope for both recovery and a return to public order.

But critics of this approach, which researchers call “treatment first,” warn that it often ends up warehousing people rather than helping them truly reintegrate. The underlying cause remains untreated.

Commissioner Greene lists many reasons people become unsheltered, and he’s not wrong—but he’s talking about proximate causes, not ultimate causes. Which is to say, he never mentioned the one thing that best helps people avoid homelessness:

A home.

The housing math

The problem with the shelter approach is that it’s temporary. It’s like pulling drowning people out of the ocean into rinky-dink lifeboats where they get to hang out for a bit with a towel before being dumped right back into the ocean again. Even if we delivered perfect addiction and mental health services to everyone who needed them, we’d still have a homelessness crisis—because we don’t have enough homes.

New Mexico is missing tens of thousands of housing units—we’re doing much worse at this than our neighboring states. In this context, people with mental illness or substance-use disorder simply can’t compete for the few homes that exist.

Think back to the “musical chairs” analogy from Part 1: When there aren’t enough homes, some people will end up homeless. It’s just math.

So people get treatment: where next?

We have abysmal behavioral healthcare in New Mexico: “Our prison system is the number one behavioral healthcare provider in the state,” said Sen. William Sharer (R-Farmington) during February testimony supporting a bill to rebuild the state’s behavioral health system. “It probably ought not be that way.”

Probably it ought not. But let’s imagine we did fix it: We open the world’s best treatment center tomorrow. Everyone in the state who wants help gets it and is ready to rebuild their life.

Where exactly are they supposed to live after they “graduate” from treatment?

With tight rental markets and median rents nearing $2,500 a month, even people in recovery with jobs struggle to find housing.

That’s why focusing primarily on treatment yields disappointing results. In contrast, cities that have prioritized housing supply have made real progress.

Compare Dallas and Houston: similar poverty and addiction rates. But Dallas saw a 35% increase in homelessness since 2011, while Houston saw a 29% decrease. One big difference is that Houston tackled the problem on the supply side, building 10.2% more housing units over five years.

“If you have a homeless person and you put them in houses and provide support, 92% of them will be stable,” one Houston program manager told KERA News. “We became a test site, with tremendous help from HUD.”

The cart before the horse

This doesn’t dismiss that individual circumstances can play a role in homelessness. But decades of research show that the behaviors we see are often results of homelessness, not just causes.

The trauma of losing housing, sleeping rough, and navigating street life can trigger or worsen mental health conditions. People may turn to drugs to cope with the stress, stay awake for safety, or self-medicate for untreated conditions. It’s nearly impossible to maintain sobriety, attend appointments, or manage chronic illness without housing.

We often have it backwards. Instead of “people are homeless because they’re addicted,” the reality is often “some people become addicted because they’re homeless”—or their substance use spirals once they lose stable shelter.

Finland’s model: Housing First

A more successful approach to homelessness—proven in Finland and increasingly adopted in U.S. cities like Houston—flips the traditional model on its head. Instead of requiring people to get sober and mentally stable before receiving housing, “Housing First” provides stable housing immediately and offers wraparound services to help people maintain it.

Finland nearly eliminated homelessness using this approach, achieving 85% success rates while spending less than traditional treatment models. It works because it’s easier to recover when you have a safe place to live.

Housing First recognizes what should be obvious: Asking someone to get sober while sleeping in a tent, or to manage a mental-health condition while constantly watching their back, is setting them up to fail.

(For criticisms of Housing First, and responses to those criticisms, read here.)

Why prevention beats rescue

Even Housing First, which works well for people already unhoused, is still treating symptoms. The most cost-effective interventions happen before people fall into homelessness.

It’s like trauma care: A well-staffed ER will save lives, but preventing the car crash is always better. In housing, prevention means:

Eviction prevention programs that help people stay in their current housing

Emergency rental assistance before crisis hits

Utility assistance to prevent shutoffs that can trigger housing loss

Family support services addressing domestic violence and other precipitating factors

Most important: ensuring adequate housing supply so people have options when life throws curveballs

When I interviewed Los Alamos County’s Social Services for this article, they were distributing ten food boxes per week—up from just a couple. “Nearly everyone now says yes, I could use that food box,” staff told me. This surge was a symptom of the growing number of people on the edge—still housed, but barely. When there’s not enough money to make it through the month, the rent eats first.

What this means for northern New Mexico

Commissioner Greene’s plan comes from a genuine, shared concern about a real crisis. As he wrote, Santa Fe needs 300–500 beds, and shelters are strained. Services matter for those already experiencing homelessness.

But if we want to solve the problem, not just manage its symptoms, we need to think bigger. The visible crisis on Cerrillos Road isn’t separate from the housing pressures pushing teachers, county workers, and fixed-income retirees to the edge. It’s all part of the same shortage.

The most effective intervention isn’t bigger treatment centers. It’s ensuring people have housing before they hit a crisis.

That requires serious housing investment. In Los Alamos, that means land-use reform and speedily building apartments, “shoeboxes,” and duplexes like we did back in the early Cold War. In Santa Fe, it means moving past height limits and “historic character” arguments that block working families from living there. (For a great discussion on how historic character and sustainable development can co-exist, please see this Homewise talk with local author Chris Wilson.)

Donating to shelters in Santa Fe and Española is good! But if residents in wealthier neighborhoods aren’t also supporting housing in their own backyards—or worse, if they’re blocking it—then they are sending money to rescue operations while ignoring the broken system that created the emergency. It’s like sending ambulances to the bottom of a cliff while refusing to fix the guardrail at the top.

Treatment and services matter. However, to require fewer rescues down the line, we have to fix the housing system that’s producing this crisis.

ICYMI, here’s part 1:

Why are there so many homeless people in Santa Fe?

This is the first in a four-part series on homelessness in northern New Mexico. When I first started reporting for Boomtown, one of my earliest discoveries was that Los Alamos—despite being one of the wealthiest counties in America—does indeed have unhoused people

Next up: The hidden emergency of housing insecurity affecting thousands of northern New Mexicans who never show up in homeless counts—but are one setback away from joining them.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jdieu7466r9hdv38/p/preview-a-mistake-of-matter?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=5odzap