Some notes on supply skepticism

People really want a different theory than 'building more housing will cut costs'

Supply skepticism is a very common reaction whenever I and other affordability advocates suggest that building more housing will bring down housing costs. For e.g., this response to a discussion I started on Reddit (see the whole debate here):

Housing costs have gone up dramatically in the last few years, drastically outpacing the previous rises in housing costs. It’s directly attributable to investors buying homes during Covid low rates and [short term rentals].

In other words, this person is saying it’s not constrained housing supply that’s causing huge price increases, but corporate power, the accident of Covid, and simple greed. Lots of people believe this, it has emerged! And they do not believe supply/demand has anything to do with prices. So let’s get into it.

The rent crisis predates Covid by years. Research by

shows that regressive rent inflation (i.e., where rents go up more in poor than in rich neighborhoods) dates at least to 2015 and has moderated since 2020. The most punishing rent increases for low-income households were already well underway before any investors could have anticipated a pandemic.Housing was unaffordable before Covid. Housing journalist

described pre-Covid conditions as simply “not affordable” with “really high rates of people who could not afford rent well before Covid began.” The crisis was already in full swing in America’s job-rich cities. You can see that discussion with Ezra Klein here.Investors were attracted by the crisis, and probably worsened it, but didn’t cause it. According to the 2024 Urban Institute report “Place the Blame Where It Belongs,” institutional investors “do not change housing supply or demand” and “periods of rapid rent increases correlate with periods of greater household formation coupled with supply shortages, which attract, but are generally not caused by, institutional investor buyers.” Covid’s work-from-home shift created sudden demand for more space, but this hit a housing market already constrained by years of underbuilding.

Interest rate timing doesn’t support the investor theory. While Covid brought historically low rates, the housing shortage had been building since the Great Recession. We’ve lost millions of vacant homes that used to keep rents stable—when you add up all those missing vacant units since 2007, it equals about three times what builders construct in an entire year today.

The way Erdmann explains it, vacant homes function like slack in the system—when there aren’t enough of them, rents rise rapidly. Even if builders tripled their output for a full year, it would only restore the housing market flexibility we lost after 2007.

The regional pattern contradicts the investor narrative. If investor buying were the primary driver, you’d expect to see the biggest price increases in markets where investors were most active, right? Instead, prices were already highest where housing supply was most constrained, regardless of investor activity.

A supply problem requires first and foremost a supply solution. As that UI report concludes, “A massive supply shortage is causing high home prices and rents, and the way to fix it is to build more housing.” It is sort of amazing how resistant people are to this conclusion! Any other factors, including investor activity, are “of second-order importance” compared to the fundamental supply-demand imbalance, says UI.

The evidence suggests Covid and low rates accelerated an existing crisis rather than creating a new one. This does not mean supply is the only lever to get to affordability, but it’s the strongest one, and if anyone believes otherwise they need to build a case supported by facts and evidence.

Now, let’s get to Airbnb

Short-term rentals (STRs) like Airbnb are another popular scapegoat. And I get why: It’s not always fun to live near them, and it’s infuriating to think of “outsiders” coming to your city and taking over nice neighborhoods. However:

STRs are a tiny fraction of the housing stock. Even in tourist-heavy cities, short-term rentals typically represent a fraction of total housing units. In most markets, they’re a rounding error compared to the millions of missing housing units documented in the research.

STRs are being blamed for century-old problems. According to this University of Missouri law review, “New York City has struggled to offer affordable housing for the last 100 years, and San Francisco has struggled for the last 30” - yet “Airbnb’s status as a scapegoat for problems it did not create has led policymakers to mis-regulate it.”

The timing doesn’t match. Airbnb launched in 2008 during the Great Recession, when housing construction was already collapsing due to the financial crisis. The housing shortage that followed was driven by years of underbuilding after the recession ended in 2009. The same law review notes that if STRs were the primary driver of housing costs, “we should have seen housing crises emerge in the early 2010s in proportion to Airbnb adoption,” but instead we see longer-term patterns rooted in supply constraints that predate the platform.

Many STRs wouldn’t work as long-term rentals anyway. As the Urban Institute says, short-term rentals “provide a valuable service by increasing options for households who cannot commit to a more permanent lease or for visitors,” and properties optimized for weekend tourists often aren’t suitable for permanent housing even if converted back.

The constraint is still supply. Even if every STR became a long-term rental tomorrow, you’d still have far more people competing for housing than available units in constrained markets—which is why the housing shortage predates and will outlast the STR phenomenon.

I’m not an Airbnb apologist. STRs absolutely can create localized issues worth addressing, but they’re a reaction to housing scarcity rather than its primary cause. People would not be investing in STRs without the housing supply shortage. The same point is true of every other kind of investment in housing: when we make housing a luxury product, like diamonds, that only the wealthy can get their hands on, we’re incentivizing all these behaviors we say we don’t like: Airbnbs in your neighborhood, house-flipping, investors turning homes that were once ownership homes into a rental house. If diamonds suddenly fell from the sky like rain, they would be a lot less valuable and nobody would invest in them.

If we want to make housing more affordable, we need to make it … okay, not rain down from the sky—it might squash a wicked witch or two, but a true glut would cause problems. We need balance. Housing prices will normalize when we allow housing to meet demand. This is the most obvious conclusion from Econ101. For some reason that truly mystifies me, a large number of otherwise intelligent people reject it out of hand. I don’t understand why. It is frustrating and weird.

Think of it like blaming egg farmers, or the grocery store, for charging higher prices for eggs—when the real cause is the avian flu that wiped out the birds. Even if every Airbnb went back on the market as a home for sale tomorrow, you’d still have far more people competing for housing than available units. Especially in constrained markets like we have in New Mexico. And that fierce competition for a limited resource is going to drive up prices. Housing may be complicated, but the economics of supply and demand is pretty simple.

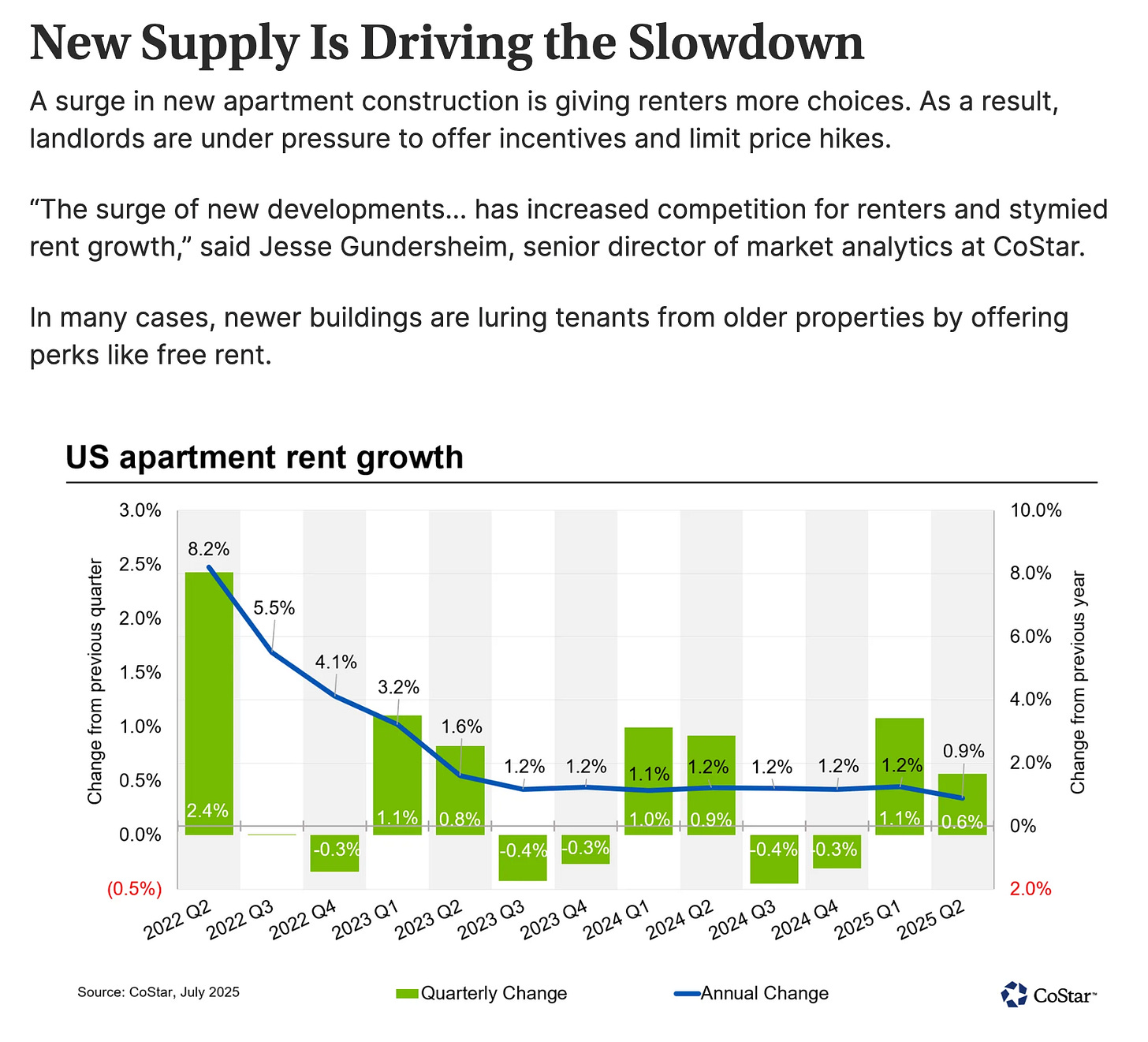

Building more housing actually works

The data show that increasing supply reduces costs. Cities that have embraced housing construction see real results: Houston reduced minimum lot sizes and created a townhouse boom with “34,000 new units from 2007 to 2020 that were affordable for those around the local family median income,” according to this Pew analysis.

Minneapolis eliminated parking requirements and allowed multifamily housing on commercial corridors, seeing “a sharp 14.5% increase in the number of homes added from 2017 to 2023, building at about six times the rate of New Mexico.”

The Pew analysis found that zoning reforms like these have improved affordability, in sharp contrast to New Mexico (with restrictive policies), which saw a 60% rent growth compared to Houston’s 13% and Minneapolis’s 2% decrease in rents. As the Urban Institute research shows, “new construction frees up apartments in a variety of neighborhoods across the income spectrum, and therefore provides additional competition that can lower prices in neighborhoods across a city or metropolitan area.” The solution isn’t to double down on preventing STRs—it’s to build more housing.

Note: This piece was slightly updated to correct a statement about the Great Recession and Airbnb’s launch.

This is a great article that I'll definitely reference in the future.

I do have one potential objection in mind, and I'd love your take on it. What do you think about real estate being seen as an investment?

It seems to me that all asset classes must continually get more expensive at a rate that outpaces inflation in order to be investments, and so the presence of any housing investors is a huge problem for affordable homes in general. In other words, in order for housing prices to drop (or at least only appreciate with the general rate of inflation), we'd have to make so much housing that real estate would no longer be seen as an asset class at all. Doing so would definitely piss off the institutional investors, whose livelihoods are dependent on housing becoming more expensive, and who thus have a vested interest in artificially constraining housing supply with zoning regulations and other such nonsense—and they definitely have more lobbying power than us.

Would love to know your thoughts!

Excellent summary of these issues