Republicans push massive public lands sale as housing solution

Western governors split, insurance companies laugh

Senate Republicans have found a bold new strategy to fix the housing crisis: Sell off millions of acres of national forests, hiking trails, ski resorts, and wildlife corridors to the highest bidder. Because if there's one thing Americans are clamoring for, it’s more private luxury cul-de-sacs in fire zones and fewer places to hike and camp.

The pitch

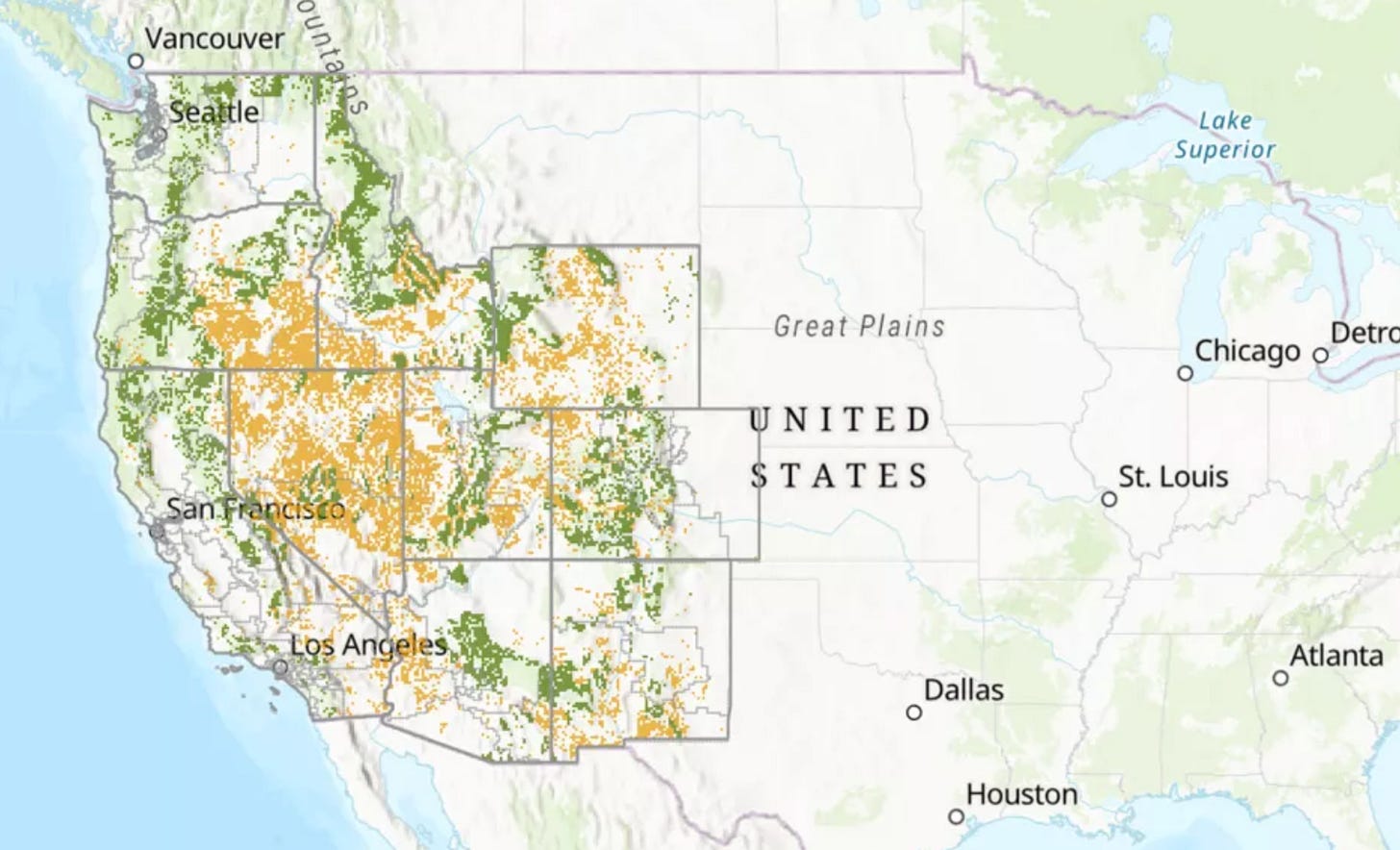

Utah Sen. Mike Lee’s provision in the GOP’s budget reconciliation bill would mandate the sale of 2 to 3 million acres managed by the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, while declaring a jaw-dropping 250 million acres “eligible” for future disposal. That’s not a typo—that’s nearly the size of Texas. The bill’s authors claim the move will ease the West’s housing shortage. Also, conveniently, it would raise cash for tax cuts.

What the bill doesn’t do: require that any of this land actually be used for housing. And certainly not for workforce housing. Although Lee talks about a housing crisis and American families being “crushed,” there are no income targets, no affordability covenants, no site planning—just an open invitation for more luxury vacation homes, Airbnbs, and private ranch compounds.

“There is no provision to prevent lands sold under Lee’s bill from being developed into high-end vacation homes,” warns a letter signed by nearly 150 conservation and public access groups.

The politics

Lee’s big idea is being sold as housing policy, but it seems more clearly to be a land liquidation bonanza disguised as reform. The Wilderness Society calls it the largest single sell-off of national public lands in modern history, all to finance tax breaks that disproportionately benefit the wealthy.

In New Mexico alone, more than 14 million acres could be affected—including the Sandia Mountains and the Sangre de Cristos. Because apparently what we really need is more high-risk exurban sprawl, fewer places to hike, and destroyed watersheds.

Governors divided

The split was on evidence at the Western Governors Association meeting this week in Santa Fe. Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon praised land transfers for helping cities “grow,” calling the federal checkerboard of land ownership an obstacle. He wants to let towns chip away at it—piece by piece.

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham wasn’t having it. Calling the process a “nonstarter,” she said bypassing local input and public access protections is a problem for any state that values its land—and its people.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis added that wholesale land sales would be a “devastating blow” to the region’s quality of life and economy. Westerners, he noted, tend to like being able to use their public lands.

Unbuildable by design

Of course, even if the land were sold for housing, there’s a glaring omission from the discussion: any homes built in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) will, from now on, probably be uninsurable.

As wildfire risk escalates across the West, insurers are raising premiums, canceling policies, and fleeing entire regions. In Los Alamos County—where multiple major fires have already burned—residents are being dropped even after hardening their homes and clearing defensible space. As housing becomes uninsurable and unfinanceable, residents are in a fierce pickle.

“When insurance companies pull out, people can’t sell, can’t rebuild, and can’t get mortgages,” said state Sen. Peter Wirth at recent legislative hearings. “We are locking homeowners into ghost towns.”

And yet this bill proposes building more homes exactly where no one can insure them.

Fire country fantasies

Advocates of acquiring federal land for private housing have a strategy: build ever-deeper in the woods, ignore climate science, and act surprised when everything burns. Then repeat. California’s Camp Fire created price shocks 100 miles away as displaced families scrambled to find housing. And even that disaster hasn't stopped similar developments elsewhere.

Los Alamos fire officials have warned that “we are never out of the woods”—and now lawmakers want to literally build more housing in those same woods.

Meanwhile, insurance companies use satellite data to automatically flag homes for cancellation, regardless of homeowner effort. You can’t out-rake your way out of systemic risk.

The local pattern

People who are angry at Mike Lee might want to look a bit closer to home. This federal push for land sales isn’t happening in a vacuum. In Los Alamos, officials have spent decades asking the federal government for more land rather than allowing appropriate development within existing boundaries.

In their 2025 federal priorities document, Los Alamos County is still asking Congress to “create a new land transfer law to convey land to the County to enable the County to make land available primarily for housing.”

This is the same community that in 1982 rejected a modest infill project in White Rock—a proposal to rezone 12.9 acres from large single-family lots to very slightly denser development that would have created 45 homes instead of 25. Residents called it “incompatible and inappropriate,” preferring to look toward the canyons for future growth.

Planning and Zoning at the time called the moderate density plan good, but elected officials overrode them, saying, “They are trying to find a way for the future of Los Alamos but this is the wrong way. We need Rendija Canyon.”

This pattern has played out over decades: Rather than allow appropriate density in safer areas, go for more sprawl. Acquire more federal land, build in the wildfire zone, then act surprised when fires destroy homes and insurance becomes unavailable.

Whether it’s DOE land or Forest Service land, it’s still public land. And it’s still the same bad idea.

Real solutions don’t make headlines

We should stop pretending this is about affordability. If housing were the goal, we’d be talking about infill, zoning reform, and land use modernization in places with existing infrastructure—like White Rock, where decisions like those made in 1982 keep usable land locked up.

Even the Western Governors Association’s own housing report doesn’t mention land sales. Instead, it blames “zoning and land use laws that impede housing development” and bureaucratic permitting as major obstacles.

In other words, we don’t need more land. We need to stop misusing the land we already have.

What’s next

The Senate is expected to vote on the broader GOP budget package before the July 4 recess. Environmental groups, tribal leaders, and public access advocates are pushing governors to oppose the land sale provision, while its supporters continue to wrap it in a shaky housing narrative.

“This land belongs to all of us—they don’t belong to rich millionaires,” said Santa Clara Pueblo Gov. James Naranjo at a protest outside the WGA meeting. “We’re fighting for Chaco, for Bears Ears, for all of it.”

If lawmakers want to address the housing crisis, they should try doing the hard, unsexy work of fixing the systems we already have. Because paving over sacred land in a tinderbox to build uninsurable luxury housing isn’t a housing solution—it’s a giveaway wrapped in a gas can.

There's a lot going on right now with the administration's "Flood the Zone" strategy, so I'm glad to see attention to this issue picking up. Thanks for writing so much about it, and drawing the connections to our local community. It needs to be made very clear that their goal is selling off our nation's lands to the highest bidder. They want to open the floodgates so that prices collapse and some of our most cherished shared resources can be bought up and owned, privatized, all at once, and regular people never have access to them again. The billionaires clamor for an opportunity to own more, and more, and they're angry that there's land allocated for the rest of us, and that the best private resorts and retreats are already owned. And in case anyone is under the very naive delusion that this would be opened up to everyone, just consider the simple logic of whether you think a state government would rather manage selling 10000 small lots to 10000 buyers, or one large lot to one large buyer. Not only do they want to own it all, they want to do so as cheaply as possible.

Historically, one of the reasons some folks from back east (e.g., Texas) move to New Mexico, especially in retirement, is because of the wide availability of public lands. Want to hunt back east? You often have to own land, or know someone with land, or in the Midwest basically trip over other people on the crowded public lands. This is why those states restrict hunting to shotguns or rifle cartridges that don't fly as far, because the risk is too high of a bullet randomly finding a person if fired in a forest. Want to go for a hike, maybe backpack on the way? Even if you live in an area where that's nice to do, the land to do it on is sparse, and keeping illegal outside of private campgrounds. Everything is owned, everything comes with a cost.

And one thing people love and appreciate about being here, maybe even take for granted, are the national forests, which have been conserved by the Forest Service over the last 120 years of its existence. We've learned through mistakes that these forests in the arid Southwest cannot grow back. Once the land is deforested and over-grazed, nothing but desert remains, our natural resources steadily dwindle, and the region gets hotter, and drier. The trees here aren't like forests in the Southeast, which go from sapling to harvestable in 20 years. We don't need these lands opened up to people who don't understand that. My house is a short walk from White Rock Canyon, above the Rio Grande. Over a century ago there was a lumbermill down there on the river, and even a town called Buckman: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckman,_New_Mexico. I don't know exactly where the lease was for the Buckman lumber operation. But I do know what after four years they had exhausted it and the town soon ceased to exist.

And the fact that they're claiming these lands, which are sparse, often far from jobs, utility hook-ups, and the other services we depend on for modern life are going to solve the housing crisis is the clearest indicator that it's just a lie. The reason these places remained forests is because they were largely deemed not suitable for housing. We have a cabin in one of those green polygons in the Sandias. At 8000' of elevation, we shut it down every October, and look forward to seeing it again in May. It's not far as the crow flies, and of a similar age, to Oppenheimer's cabin, "Perro Caliente," which was his inspiration for suggesting New Mexico as a location for the Manhattan Project. The roads there are largely impassable in winter, and while we could ski in (no snowmobiles allowed to protect the forest), or maybe even make it in our car given how little snow we now receive due to climate change, the cost of heating it in the winter is massive, and propane delivery is not exactly predictable. Last time I checked "housing" usually needs to be usable for more than six months a year.